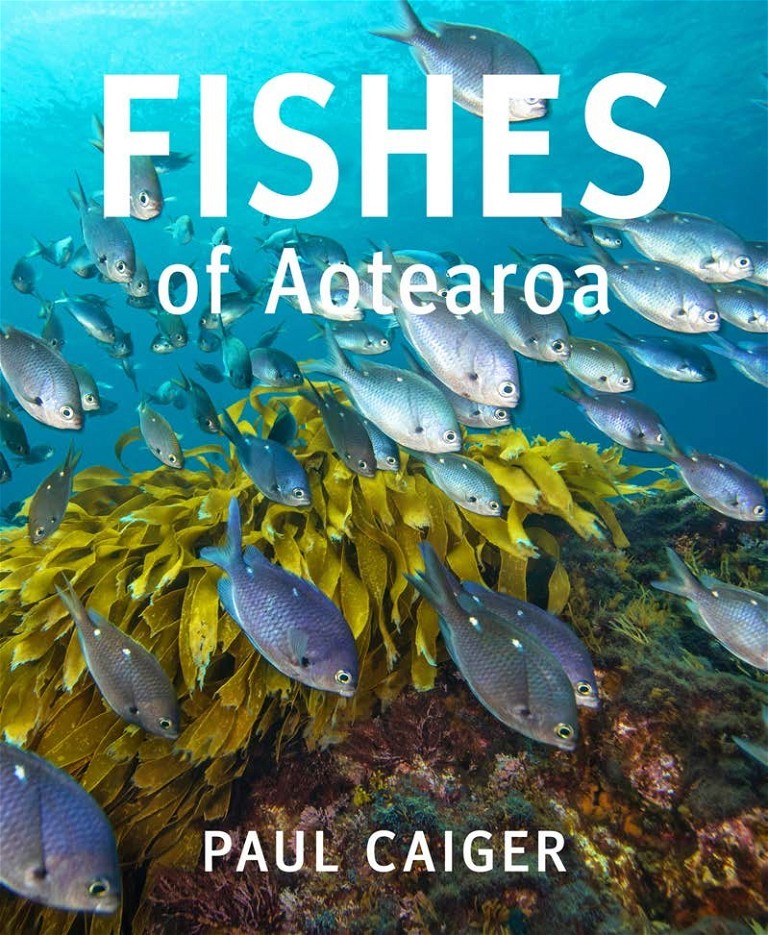

FISHES OF AOTEAROA BY PAUL CAIGER

Review by Nick Jones

Published by Potton & Burton, RRP: 79.99.

As an obsessive young angler, I used to spend countless hours poring over any literary work about the marine world. One book I remember fondly, holding pride of place on my grandparents’ bookshelf, was the New Zealand Sea Anglers’ Guide. First published in 1960, with imperial measurements and no photographs, I loved going through all the fish species, wondering if I would ever have the opportunity to snag the mysterious creatures illustrated on the dusty, tanned pages.

Luckily, there are now fishy books that are far less demanding on one’s imaginative abilities, such as the newly-released Fishes of Aotearoa. Author Paul Caiger is an accomplished marine ecologist who has 25 years of scuba diving under his (weight) belt. Dovetailing with Paul’s science background has always been the creative outlet afforded by photography, and this book is a representation of his two passions, blending superb underwater photography with fascinating natural history stories.

Although this book is intended for a general audience, it is written by a scientist and I think some laypeople might bemoan the lack of a glossary. Similarly, the absence of an index or comprehensive coverage of NZ fish species means this book is not an A-Z species guide to be used as a reference for an unusual capture.

Nevertheless, for a reader like myself with a rudimentary to intermediate understanding of the marine world, there are intriguing learnings to discover in every section. Covering freshwater, inshore and offshore habitats and the Kiwi fish species that live within them, this 240-page hardback book with dimensions similar to this magazine would make a perfect gift or addition to the coffee table.

Book excerpt

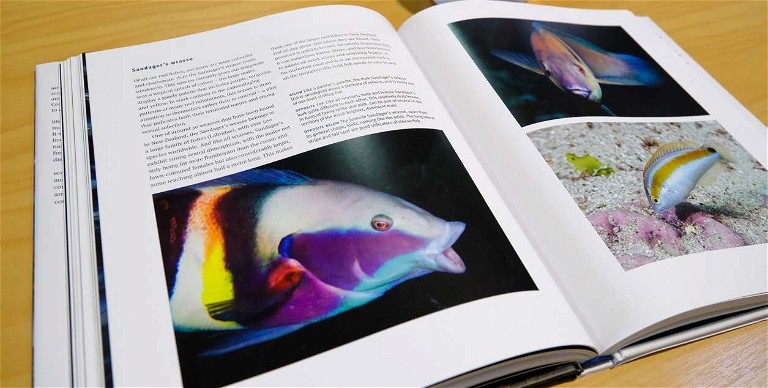

Of all our reef fishes, not many are more colourful and charismatic than the Sandager’s wrasse (Coris sandeyeri). This species certainly gives our temperate seas a tropical splash of colour – the large males display a gaudy palette that includes purple, turquoise and yellow. In stark contrast to the camouflaging patterns of many reef inhabitants, this serves to draw attention to themselves rather than to conceal – a ploy that indicates both their territorial nature and strong sexual selection.

One of around 30 wrasses that have been found around New Zealand, the Sandager’s wrasse belongs to a large family of fishes (Labridae), with over 500 species worldwide. And like all wrasses, Sandager’s exhibit strong sexual dimorphism, with the males not only being far more flamboyant than the cream and fawn-coloured females but also considerably larger, some reaching almost half a metre long. This makes them one of the larger reef fishes in New Zealand, and on any given dive where they are found, their presence is quickly known. An overtly inquisitive fish, it can sometimes follow divers, and has been known to nibble on mask straps and unwitting fingers. A fin-disturbed sand patch or an overturned rock is all the invitation this bold fish needs to race in and snag a morsel, further explaining the diverpositive behaviour.

But long before humans swam around under the waves, the large male Sandager’s wrasses were there, defending a territory on the reef, and within it a harem of females. Young, yellow-striped juveniles are also in attendance. These young fish, also females, regularly serve as cleanerfish for other fish species, and it is a common sight to see them being chased and pestered by legions of demoiselles or trevally looking for a parasite clean.

One of the most remarkable traits of this fish is that it spends the night buried in the sand. So, at dusk, the large male wrasse begins to search for a suitable night spot (as do all the Sandager’s wrasses), hovering over a patch of sand with just the right grain size. And then in a flash he disappears in the sand, completely submerged, the only signs the occasional puffs of water jetting out as his gills work. A small coating of mucous gives slight protection against ‘bed bugs’ (aka parasitic invertebrates), but it also lessons his smell for more serious predators above the sand. This mucous layer is similar to the closely related parrotfishes of the tropics. And after a peaceful night’s rest, with the rising sun, he lifts out of the sand into the breaking of a new day on the reef.

Despite the coincidental behaviour of sand diving, the name ‘Sandager’s wrasse’ actually has its origin in a person – Andreas Fleming Stewart Sandager, who was the lighthouse keeper on the Mokohinau Islands in the late nineteenth century. Being a fond naturalist, he was the first to collect a specimen of the wrasse and it was named in his honour. Recent surveys show they are even more abundant at the Mokohinau Islands than at their protected neighbour, the Poor Knights Islands, and as such, the home of their name is also quite possibly home to the highest densities of Sandager’s wrasse in the world.